MUSEUM QUEST

ZOOLOGY

Disclaimer: Unless otherwise specified, no copyright claims to photos, illustrations and maps.

"1) Today I’m going to show you the different venomous snakes that live in Louisiana and the non-venomous snakes that look similar to them. I'll show you foolproof ways to identify venomous snakes so that when you leave here, you’ll know instantly if a yellow, red and black snake is a coral snake or a non-venomous look alike. You’ll also learn how easy it is distinguish a venomous cottonmouth from harmless water snakes. I’ll also show you how to identify copperheads, timber rattlesnakes and pygmy rattlesnakes. This is an informal talk so I encourage you to stand up go over to the snake tables over by Joe Incandela at any time. We’ve brought lots of museum specimens and some live snakes. You can try your hand at using a snake stick with some harmless species if you’d like to.

2) After the identification segment, I’ll explain what to do in the event of a snakebite and how to avoid snakebites. I’ll share some statistics about snakebites in the US. I’ll also talk for a bit about how venom works and why a bite from a coral snake is different from the bite of a viper.

3) Before we go over identification and safety, I’ll tell you my theory about why people are suddenly seeing coral snakes in this parish….."

"I know that coral snake sighting in Crowley are part of the reason why I’m here. I read everything that I could find about it in the press. What was witnessed here would surprise just about anybody. For several highly venomous snakes to turn up where they’d never been seen before and for one of them to appear close to a school is unsettling. They are highly venomous snakes. The state herpetologist, Jeff Boundy, stressed this in the papers. Jeff Boundy also stated that this is not an instance of a population explosion. This is not, as several newspapers called it, an "outbreak". Another Louisiana herpetologist who was quoted in the papers, Dr. David Sever, agrees. I agree too. Not because Dr. Sever is a member of my thesis committee but because it isn’t unusual for different snakes to become newly visible following certain kinds of land development projects. The snakes didn’t suddenly arrive and the population is almost certainly smaller now than it was prior to development and it isn’t about to grow. The difference is that now, some of the cover has been pulled back.

Something very similar happened in my hometown. I grew up in a rural area, on land that was surrounded by a nature preserve on two sides and 32 acres of forest and meadow habitat on another side. I snaked there all the time. There were two species that I found there easily, and six species total. In 2002, the town started to develop the land and by 2003 it was converted into a huge recreational park with soccer fields, baseball fields and a gravel parking lot. But I didn’t stop finding snakes. One species, the black rat snake, which I’d seen there on 3 occasions prior, began to show up almost every week. There were two individuals, who frequented the same areas, both near tree-lines, where they could travel with ease, bask in the sun and quickly seek shelter. I also saw black racers more often, usually on the mowed grass within a few meters of the trees. They were there all along, they were just better hidden before the construction. I can also find garter snakes more easily now since they like to bask near fallen logs on the sides of the fields. There’s an opening in the canopy and they’re using it to get sunshine. When they see me coming, they rush beneath the logs. There are old baseballs around the logs where the snakes bask, hit from the adjacent field. That’s how close they are to people. The copperheads disappeared from the territory that was directly developed but they continued to live on some higher ground that the bulldozers didn’t touch, that is adjacent to the parking lot, which for awhile, remained my go-to place to find copperheads because it is great habitat. It wasn’t until 2013, around the time that the coral snakes began to make their appearance in Acadia Parish, that I stopped seeing and hearing the copperheads. They seem to have all but disappeared from the land. If its any reassurance, for ten years, those copperheads lived discretely, in an area 30-60 meters from a park where dozens of people came to play sports every day. Not one person was ever bitten because of it."

Holding on to snake like this is called “tailing”. To tell you the truth, a lot of professional snake handlers, including scientists, practice tailing in their labs and in the field. The difference is that they protect themselves with a snake hook. Over there, by the display tables, Joe is demoing snake handling using two types of hooks and snake tongs. Can you hold up your tools Joe? If anybody want to go over for a closer look, remember that this is an informal talk so please feel free to do so at any time. "

"I censored this man to protect his identity although, I doubt be would feel too embarrassed because I literally found these photos on a website called datehookup.com. So this is something that he’s obviously proud of. I wont spend much time on this slide because the message here is pretty clear: this is NOT something that any of us should be doing. The problem with draping a coral snake over your face is that there is literally nothing to prevent the snake from biting you, which would be a disaster, given the close proximity of your face to your brain. Coral snake venom specializes in attacking the central nervous system which we’ll talk more about later.

The way that he’s holding onto the adult snake in the smaller picture is also very ill-advised. There are safe ways to handle venom snakes that don’t involve your hands. This is a lot safer than the face dangle but it’s still dangerous because all coral snakes, babies and adults ARE FULLY CAPABLE of doubling up and reaching the hand if they’re held this way. When they do double up, it happens extremely very fast. This man is counting on his own reflexes being faster than the snake’s. Another problem with Romeo here, is that his eyes are looking up, directly at the camera lense. He is not watching the snake.

"In the United States, there are four basic ingredients that are necessary to get a coral snake. You have to have all four. If any are missing, its simply another snake! There are no exceptions. Then there are additional ingredients that characterize the snake that we’ll go over but its extra information since the color scheme criteria works so well.

In louisiana, the red bands are generally a dark red, with some black scales intermixed. The yellow rings are thin. There’s a broad yellow band on the head and the nose is always black. the eyes are black and tough to see. Coral snakes max out at about 45 inches which is a little longer than this yardstick. Now that’s the world record. 45 inches is in some field guides because it has to be included but you don’t ever have to prepare for a coral snake that big. The biggest of the museum specimens over there on those tables are the biggest that you should ever expect to see in Louisiana. No more than 20 inches."

"This is how to identify a snake as venomous in the United States.

Anywhere in the world, exactly two pairs of facial openings are characteristic of a venomous snake. In Louisiana, vertical pupils are indicative of a viper. This could be a rattlesnake, cottonmouth or copperhead. There is no non-venomous Louisiana snake with vertical pupils. If you’re close enough to see that kind of detail, round pupils can often be identified from a very safe distance. Round pupils are usually fairly big and the eyes are easy to see. From that same distance, vertical pupils can sometimes be a little harder to identify. The rattle of course is a tell-tale sign that the snake is venomous. It’s foolproof if you see it. But it’s still important to consider all of these field markings, especially because the rattle might not be audible or visible at the time.

Coral snakes are the only venomous snakes with round pupils. But you cant see the pupils unless you are too close, so for coral snakes, pupil shape is useless as a field mark. The pupils of a coral snake, which are round, wont even be visible because of their small size and black coloration. The eyes and and head are the same color."

"Here's why it is worthile to know."

"The eye stripe is absent. These photos don’t do these snakes justice. In Louisiana, their heads can be a rich orange. They are very attractive and very well camouflaged when in their element. Recognizable by the brown/light, top/bottom countershading on the sides of the head. If you get close, you see the flat, dark line separating the top from the bottom. They have an hourglass pattern. These snakes, like all N. American vipers, tend to remain still and wait for you to move on, relying on it’s camouflage to keep it hidden and safe. You can get very close to these snakes without realizing it but fortunately, they do something very conspicuous before biting. They vibrate the tips of their tails! It’s quite loud. Most snakes around here do this. It’s meant to intimidate. It makes a buzzing sound against the leaves, asphalt, sticks, or whatever is around it. If you hear it, stop walking and try to find the snake. Then simply leave! You can run or walk, it doesn’t matter much but if you’re able to, it is better to vacate the scene smoothly, without causing a disturbance. If you hear a buzz but can’t locate the snake, study the ground around you and carefully scope out a snake-free path that will lead you elsewhere.

"That’s me, looking at a cottonmouth in Florida. It was crossing the road. The photographer is about as close to the snake as I am which is a safe distance. The photographer and I are safe, there’s no way that snake will get near us. At a safe distance, we can easily see the thick, dark eyestripe. This is a great field marker for cottonmouths. There are lots of thick-bodied brown water snakes that aren’t venomous. But if you see a thick bodied, brown-colored snake with this band, it’s a cotton mouth.

Cottonmouths eat rodents, lizards, frogs, fish and other snakes. They’re also well-known for eating animals that have been hit by cars as well as dead fish. They are hunters are well as scavengers. Though these are common snakes, death by cottonmouth is incredibly, incredibly rare. "

"Copperheads were originally reported as be rare in Acadia parish. There were no records as of 1989, although there were for the surrounding parishes. I'm aware that y'all see them from time to time. They are here. This snake has the lowest mortality rate of any venomous snake in N. America. The only copperhead-related death on record, was caused by an allergic reaction to the anti-venom. Unless you were in extremely poor health prior to being bitten, you should not need copperhead anti-venom to save your life but anti-venom aid recovery, provided that it is properly administered and there are no complications.

"QUIZ! What are we looking at? Copperhead or Cottonmouth?"

"In the Southeastern United states, more people are bitten by pygmy rattlers than by any other venomous snake. Fortunately, pygmy rattlesnake bites are very rarely fatal. It sounds cliche, but their tiny bodies, make them easy to identify. They have short, black saddle, or bean-shaped patches against a light, spotted background. Their heads have plenty of dark pigment. You should hear the buzzing of a rattler. Evidently, there were no records of pygmies from this parish by the time that this 1989 survey was made. Collectors had come and documented cottonmouths here by that time. Since this map was published, there have been plenty of records! They’re here. Fortunately, bites are extremely rare."

"Timbers are the only venomous snakes in Louisiana with a continuous longitudinal line down its back. The color of the line is highly variable but it generally clay-brown or rusty red. The width and brightness of the line can also vary but in this species, it is always there. Another timber rattlesnake field marking are the chevrons.

The line is not framed in by any colored borders, it is bare, as if it were drawn on with a pastel crayon."

"QUIZ! Which rattlesnake species are we looking at?"

"QUIZ! What are we looking at?" Answer: Not a coral snake. This snake can be ruled out as a coral snake even if you’re looking at it cross-eyed. The cream colored bands are completely sandwiched between black bands. The red and yellow never come into contact. Red touches black. In addition, the bands aren’t quite yellow but more of an off-white. Milk snakes and coral snakes prefer more or less the same type of habitats so it wouldn’t be shocking to find one in an area where coral snakes are known to occur. Milk snakes are constrictors that max out at around 4 ft. They usually prey upon rodents, lizards and other snakes. It’s a fact that milk snakes eat venomous snakes, killing them by constriction, then swallowing them whole.

When you think about it, small snakes are perfectly shaped food items for big snakes. That and their lack of claws, strong jaws and big teeth make them relatively easy to capture and swallow. Rodents are actually pretty dangerous as prey because they can bite hard, fast, deep and repeatedly. Most rodents crack with their teeth. The worst animal bite that I’ve ever sustained wasn’t from a snake, it was a squirrel."

""QUIZ! What are we looking at?" Answer: Not a coral snake. This snake has yellowish, red and black bands but like the Louisiana milk snake, the red and yellow bands do not come into contact and the yellow is really more of a whitish cream-color. If you flip them over, their bellies are totally white. If you look closely at the face of a scarlet snake, you can see that it’s nose is shovel-like, completely unlike that of a coral snake which is round. Furthermore, the scarlet snake’s nose is always red. The coral snake’s nose is always black. This snake lives in the leaf litter and under logs and debri. This species is small, maxing out at around 2 feet. It eats invertebrates, small lizards, baby rodents if it can get to them, and baby snakes."

"QUIZ! What are we looking at?" Answer: Not a coral snake. This is a totally non-venomous snake. To some, mud snakes look too bright to be harmless, but they are. They actually, have a reputation for being extraordinarily docile snakes. They’re famous for a few things: living in the swamp, eating Amphiuma salamanders and crawfish, having amazing ember-like red eyes and for being non-biters. A garter snake will bite you but this snake, almost as a rule, wont. You’d have to hurt it and even then, it still might not bite you. If a mud snake breaks character and DOES bite, you have nothing to worry about, they’re not venomous.

They do not grab their tails with their mouths, form a hoop and roll after people. Total myth. Could not have originated in Louisiana because we’re a little short on hills. That particular piece of lore may have come from Mississippi . These are some of the smoothest reptiles on earth. They are so glossy, that they feel soft to the touch. Mud snakes are also known for refusing to eat in captivity and for growing to be quite large and especially thick around the middle. "

"QUIZ! What are we looking at?" Answer: Not a coral snake. This is a cousin of the mud snake but it is much much smaller. They only get to be as wide around as a pencil. Their favorite food is lung-less salamander. Being so tiny and not being big on basking in the sun, sometimes they enter people’s homes in search of hiding spaces. I sometimes find them under indoor and outdoor doormats. If you find a ring-neck, there’s nothing to worry about, they’re completely harmless. My first pet snake was a ring-neck snake. I’ve handled maybe 50 ring-neck individuals and only one has ever bitten me. It was a 4 or 5 inch baby. Needless to say, it did not break the skin. "

"QUIZ! What are we looking at?" Answer: Not a Cottonmouth.

"QUIZ! What are we looking at? Answer: Not a Cottonmouth."

Diamondback water snake

Greenish, no eye band, round pupils.

"QUIZ! What are we looking at? Answer: Not a Cottonmouth. It's Plain bellied water snake. No eye band because everything is dark on the sides of the head. Round pupils, black lines on lips. Also, there's yellowish green happening under the chin."

"QUIZ! What are we looking at? Answer: Not a Cottonmouth. Here are two water snakes, the one on top is a juvenile. Note, the round pupils, lack of brown eye-stripe and the clear cream colored lines on the snake’s back.

Now lets move onto the snakebite stuff….”

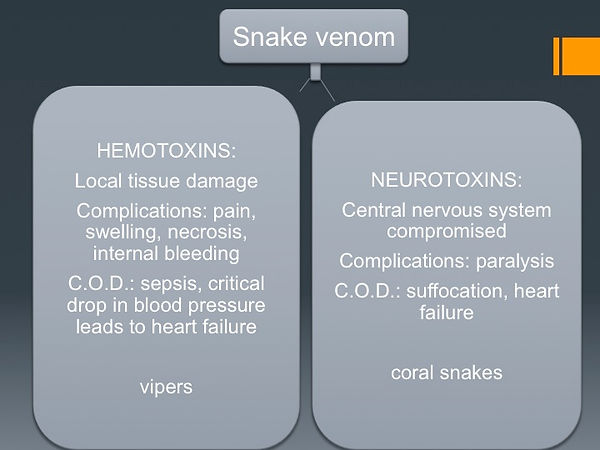

A toxin molecule is a protein that is coded for by the snake’s DNA. They manufacture it. There are two general classes of toxins that comprise the venom load of a particular snake. It’s never just one type or the other that makes up a venom dose, but a complicated mixture of many different toxin molecules from both classes: hemotoxin and neurotoxin. However, viper venom tend to be heavier in hemotoxins and coral snake venom is heavier in neurotoxins. Toxins are classed based on what kinds of cells they damage. A dose of hemotoxin behaves like a corrosive. It destroy most of the tissue that it comes into direct contact with. Blood, muscle, skin, membranes, glands and capillaries, all sustain damage when contacted.

Neurotoxins interfere with the central nervous system. They don’t rip tissues apart like hemotoxins do. Pain is not always a major factor, sometimes there is only discomfort as the victim’s body stops responding to the brain. Here, the cause of death is usually lack of oxygen.

"It’s rare when victims of viper bites do not experience intense pain. Swelling and discoloration is also inevitable when a person has been envenomated previously. A person may experience all of these symptoms and still have an extremely good chance of surviving. When bitten by a coral snake, the symptoms are different. The affects basically stem from one thing, the body is slowly paralyzed. Voluntary and involuntary functions slow down and eventually shut down. The most dangerous outcome here is when neurons that are associated with the diaphragm and lungs, cease to fire. This can happen before the heart shuts down. At this point, the victim needs a respirator or prolonged CPR or they’ll die. Even at this very late stage, people survive if they’re in the hospital at the time that they lose control of their breathing. A 7 year old Texas boy was bitten on the foot by a coral snake while in Florida with his family. His breathing completely stopped and he was put on a respirator. Three weeks later, he was released from the hospital after having made a full recovery. While the neurological effects are very scary they’re usually not permanent. Like this boy, t’s entirely possible to become very very ill and suffer no long term damage.

Coral snakes are not the only snakes with neurotoxic venom. Coral snakes have a lot of cousins and one of them, a species of krait bit my Uncle Joe in Myanmar. Joe isn’t my uncle by blood, he got his Phd along with my thesis advisor which makes him my academic uncle. I never met my Uncle Joe but we will always be related. Joe Slowinski was an accomplished Louisiana herpetologist. There’s a corn snake here named after him, Pantherophis slowinskii. Joe had collected snakes in Myanmar plenty of times before he led his last expedition. Field collection in remote jungles is emotionally and physically draining work, to say the least and Joe hadn’t slept much and he was run down. In the twilight hour, on the morning of 9/11, in semi-darkness, without looking, he reached his hand into a snake bag that someone told him contained a harmless krait mimic. He felt the snake’s teeth prick his skin as he pulled his hand out of the bag, he said “that’s a krait” and woke everyone in the camp up. Krait venom is similar to coral snake venom but a lot more potent. It became evident that this was not a dry bite when Joe started to experience the symptoms above. Before he lost his speech he gave clear instructions to his team for how to keep him alive. Unfortunately, Joe didn’t stay alive long enough to be rescued by air. When his breathing failed, his team took turns giving him CPR. They tried everything but there wasn’t anything else that they could do in the field when medical attention was so far away. he was already gone when the chopper arrived. What happened to my Uncle Joe was the absolute worst case scenario. Being so deep in the jungle, with weather preventing the chopper from reaching them and it being 9/11 and the US embassy was pre-occupied with the disaster that was unfolding simultaneously in the United States….. the odds were stacked against him. But in Louisiana, we have every advantage. A coral snake bite is simply not a death sentence. If you go to the hospital, its extremely likely that you will recover.”

"The reality of the matter is that not everyone who gets bitten needs hospital treatment. About 1 out of every 6 viper bites are dry, meaning that there is no venom payload. In all venomous snakes, venom delivery is voluntary and venom takes a minimum of a few days to replenish what’s lost during a typical bite. When it comes to humans, it’s generally in the snake’s best interest to conserve and when it senses that, it can withhold it’s venom. I’ve experienced this personally with a copperhead but I went to the hospital anyway. The ER was mostly empty. I went through initial intake, my vitals were fine so I was classified as a low-priority patient who did not need a bed right away. I waited half an hour more in the waiting room and there was no pain or swelling which meant that the bite was dry. I went home and that was the end of it. That kind of approach works fine for vipers but it doesn’t work for coral snake bites. Overall, for any bite, its smart to at least make your way to the hospital even if there’s no pain or swelling. For the record, I was gripping the snake behind the head when it twisted loose and bit me. So avoid doing that.”

"Its not a real club but it definitely sounds cool. I really recommend this book to anybody who is curious about snakebite history. It’s written by a journalist who is petrified of snakes. The word for that is ophiophobia. It means “abnormal fear of serpents”. Mr. Seal believes that he was born a hopeless ophidiophobic. Through his investigation of the reality of snakebites, he relaxes a little and becomes more at ease with the fact that snakes exist but he never fully gets over his fear, not even by the end of the book. In the book, Mr. Seal mostly writes about his interviews with snakebite victims and recounts a series of historically documentated bites.

There’s a long chapter about snake handling churches in the southeastern US which is especially interesting. It in, there are lots of examples of people who were repeatedly bitten by vipers, didn’t go to the hospital and survived to get bitten again. There are also examples of people who survived a few bites but eventually died. The most scandalous story is about an alcoholic preacher who tried his very hardest to murder his battered wife by getting her very drunk and putting a gun to her head, forcing her to provoke a big rattlesnake until it bit her several times. He then made her drive them home and he left her for dead on the porch and passed out. While the husband was asleep, the wife, who was slipping in and out of consciousness and in terrible pain, crawled to the neighbors and called 911. She survived, miraculously with all of her body parts intact. Her husband, went to prison."